PDA is popping up everywhere in neurodivergent spaces. You have probably heard about pathological demand avoidance, which goes by many other names including extreme demand avoidance (EDA) or its gentler cousin, pervasive drive for autonomy.

I wrote about PDA before. Now I want to dig a bit deeper. Ever since the term was coined in the 1980s by child psychologist Elizabeth Newson, the PDA profile has been controversial and (incredibly) is not listed as a diagnostic condition in either the DSM and the ICD.

It is generally assumed that PDA is a subset of autism, one that tends to co-occur with ADHD. In other words: those with an AuDHD profile, like my son, Carson. From there, it gets a bit fuzzy. Many clinicians are sadly not up to speed—like the psychiatrist who once diagnosed Carson with ODD (oppositional defiant disorder), a conduct disorder that has no bearing on autism. Grrrr…

PDA is not the same as wilful defiance, though it can look that way from the outside. Avoidant behaviours start as early as infancy with refusal behaviours around being dressed or placed in a car seat—that is to say, beyond the usual refusal behaviours...

A (by no means exhaustive) list of PDA traits:

refusing ordinary demands, including things they enjoy or want to do

using distracting tactics as a means of avoidance

not understanding the emotional effect of their behaviour on others

excessive mood swings and impulsivity

extreme role play and fantasy as a means of avoidance

overly controlling and dominant behaviour

lacking awareness of body signals (interoception) and emotional states

Because PDA can present similarly in those with complex trauma and attachment issues, it’s sometimes difficult to tease the two apart. Interestingly, many adopted and foster children exhibit traits similar to PDA as a response to stress experienced in early infancy or in utero. Nascent trauma can affect brain development and later present as difficulties with attention, focus, emotional regulation and meltdowns. In fact, many children with this profile go on to be diagnosed with ADD and ADHD. And just to complicate matters further, many (I would argue, most) autistic folks have a history of trauma from our lived experience.

Suffice to say, learning more about PDA has been… illuminating. At its heart, PDA is about feeling safe. As caregivers and individuals, we need to be on high alert to subtle shifts in our nervous system. Often just the perception of a demand is enough to trip the switch.

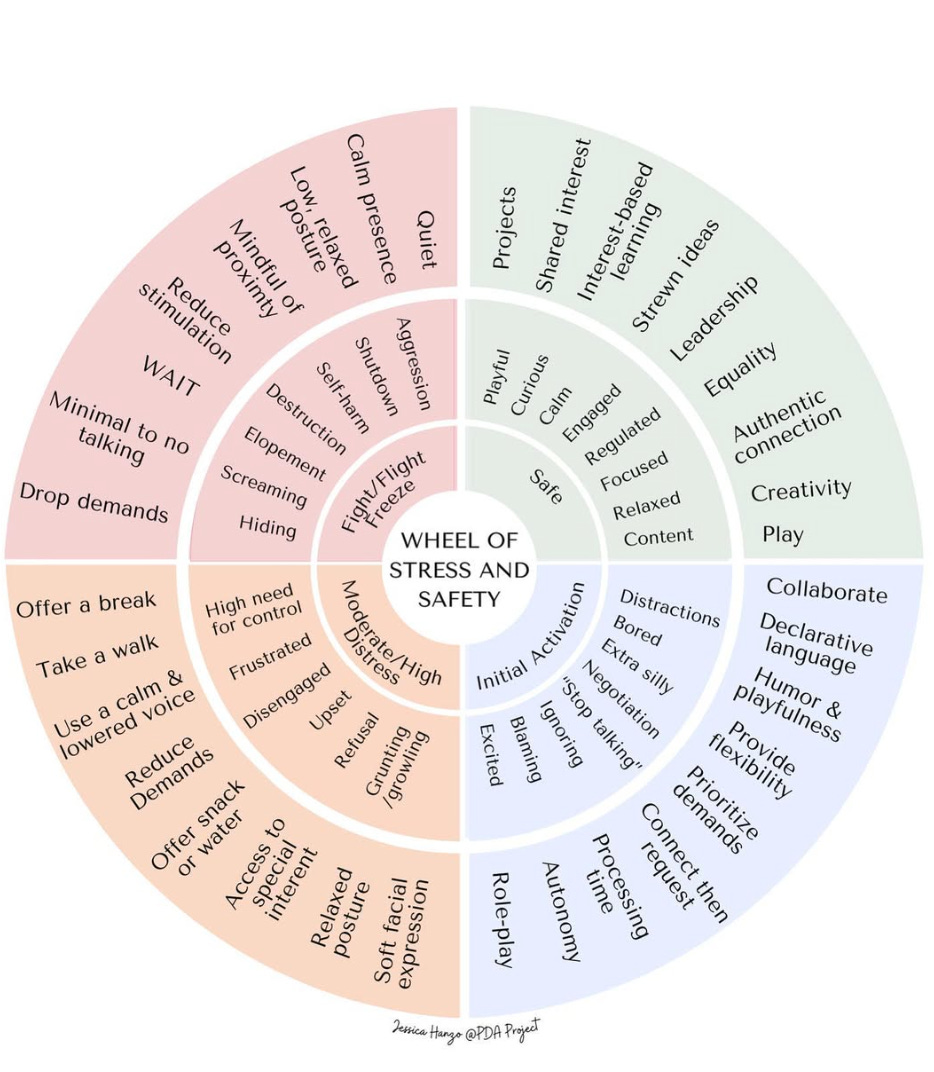

Most of the time my son is utterly charming, funny, affectionate and chatty. When triggered by a demand, though, he is prone to sudden rages and meltdowns that can involve screaming, aggression and destructiveness. Using humour or distraction to diffuse the situation can be helpful at low levels of dysregulation. Using declarative language or better yet, not speaking at all when things ramp up allows the nervous system to recover. The “Wheel of Stress and Safety” indicates stress cues and suggestions on how to respond safely.

Parenting PDA is hard, especially when you aren’t a PDAer yourself. Adopting a low-demand approach feels intensive and extreme, but it is ultimately necessary.

Part of the reason it’s so hard is that this kind of parenting runs contrary to everything we’ve been taught makes for “good” parenting. Limiting screen time, making sure your kid attends school, insisting your child eats healthy and follows basic hygiene routines like washing hair and brushing teeth, etc…

Letting go of some or all demands in many ways feels like giving up. It feels like we are failing our kids. Maybe what we need instead is a reframe. Maybe a “good parent” is simply one who supports their kids in the way that they need supporting. And in the case of PDA, that’s by fostering safety and trust, first and foremost.

Last year when Carson went through burnout, we adopted many of these low-demand principles out of desperation. I can’t say that it felt good at the time, but it did work in the long run. It allowed him to regain trust, and maintain connection while his nervous system recovered. Although he is back attending school part-time this year, Carson won’t do homework or study outside of class hours. It’s too much.

I won’t lie. There are still times when I have to remind myself that the world won’t blow up if he doesn’t graduate or learn to drive or hit any number of arbitrary milestones at a set date—if at all. His mental wellbeing is much more important than all of that.

As his mom, though, it hurts to see him miss out when his PDA prevents him from doing things he really wants to do. Yet I also see in him such a tremendous capacity for courage and resilience in the face of what he’s been through. We have been focusing on giving him as much autonomy as possible, through a mentoring program and a peer tutoring class. The boost to his self-esteem has been huge.

The good news: people with PDA often develop increased self-awareness and ability to regulate their nervous system over time. I have definitely witnessed this with Carson this past year. His meltdowns are rare and much less explosive than they once were. That’s down to a bunch of things—medication, him growing up and acquiring skills, and his parents and teachers learning to do things differently.

What is your experience of PDA? Learn anything new here?

It really is crazy to me that this isn’t part of the formal diagnosis process. I can only imagine how much easier (and less traumatizing for us all) our journey would have been if we had this information so much earlier! I somehow came across the book low demand parenting a couple of years ago and it was a game changer. That and medication, and an amazing school that fits, and learning new skills for communicating better as a family. Thank you for sharing the emotion wheel, it is really helpful to see all of those strategies in one place. PS I just pre-ordered your book. Can’t wait to read it!

On this journey! Learning how to support my kids has been revelatory for me and continues to involve so much unlearning and divesting from norms that just don’t work for our bodies or align with our values. It feels powerful to better understand my family, even as incompatibility with mainstream systems becomes more apparent. Genuinely hopeful about forging a path that will allow us to thrive on our own terms by starting with safety and building at our own pace (which probably won’t make any sense to others and letting that be ok!). Thanks for sharing your experience!